CEO of the product?

After publishing I love Product Management, I received this great question on Twitter:

@paulcothenet for example "responsible for right product/right time and all

that entails" - this seems much wider than PM as I understand it

— Ben Pickering (@benpickering) December 7, 2014When I transitioned to PM, I had no idea what I was doing (and neither did the people around me). So I started a frantic search to understand what the job was about. Good Product Manager, Bad Product Manager by Ben Horowitz was one of the first thing I read.

As I went trough it, I went through the following emotions in a very short amount of time:

- "This job sounds awesome"

- "This sounds pretty damn hard"

- "There's no way I can do all this" (to my defense, we didn't even have marketing or PR at the time)

If you're a junior PM, Horowitz's description of the PM looks much broader than your job description. I'm sure there are plenty of new PMs that are as puzzled as I was, so I hope this can help.

tl;dr:

As a junior Product Manager:

- All this doesn't apply to you (yet). It was written in a specific context and your organization and current role might not be up for it.

- It's still incredibly useful in helping you grow into your role and evaluate your organization.

- Think "How can I become the CEO of the Product" rather than "I'm the CEO of the product"

A bit of context

This document wasn't written to be shared outside of Netscape. This was 1996 and people were not yet giving generic management advice on the internet. Horowitz wrote it while in Product Management at Netscape / AOL as a training document for his own team. I'd bet he didn't expect it to be so widely circulated. When he released it he expected that people (like me) would scrutinize it to no end, so he accompanied it with this word of caution:

"Warning: This document was written 15 years ago and is probably not relevant for today’s product managers. I present it here merely as an example of a useful training document."

Of course, given the profile of the author, this warning has been largely ignored.

Why Good Product Manager, Bad Product Manager may not apply to you

Back to @benpickering's question, there are several things worth noting about Ben Horowitz' doc:

- It was written for a specific context and a specific team

- It was written by someone who was in charge of that team and could make sure the reality of the job would match the job description

- The Product Management job spans a wide spectrum of company sizes, product types, seniority and organizations.

Here are some scenarios where you shouldn't read too much into it:

Reason #1: Your company is way more early stage than Netscape was in 1996.

In 1996, Netscape was a public company. Your company may have just one product. As a consequence, the CEO of your product is the actual CEO. In this situation:

- do whatever you can to help ship the CEO's vision. Take care of the details, write PRDs, prototype, collateral, documentation, do QA...

- try to grow you role into the one described in GPMBPM

- don't ask for those extended responsibilities. Prove you can do them by doing them. A good CEO will recognize this and relinquish his role over time (unless he runs into the Product CEO paradox)

Reason #2: You're starting in PM

Your boss doesn't expect you to do all this (just yet). In this situation, figure out what's expected of you at that stage and thrive to grow into this ideal position.

As pointed out by Bubba Murarka in The Three Skills of a Great PM, starts by nailing Product Execution (i.e. Ship your first product) before worrying too much about Experimentation and Idea Validation

Reason #3: You're not really doing Product Management

You're doing Project Management. This is not necessarily a bad thing. I did this for half of my last job and I loved it. In this situation, you need to:

- Know what game you're playing and how you're being evaluated

- Get to a point where you can discuss with your management if this is the ideal situation for your company and you.

Reason #4: It's not clear what your "product" is

When you think about it, you're not quite sure you're working on a "product". There could be several reasons:

- You're starting in PM and your manager is getting you started with a subset of the problem, usually a small feature. That's all fine, just make sure you know who's owning the larger product and align with her strategy. Also make sure not to get stuck there too long and to grow into your role.

- You're actually doing Project Management

Reason #5: Your product organization is messed up (more than usual).

Sales and marketing (or the CEO) calls all the shot and you're just fighting fires. No one in product/engineering is talking to customers. In this situation:

- Figure out if you can fix it. Maybe your organization is just waiting for someone like you. Can you take the lead, talk to customers and figure out what they want?

- If you're actively prevented to talk to customers or if you're told "we know better", run away.

Why you should still apply it

That said, that piece is still pretty damn fantastic. Despite the word of caution from its author, I think it's still relevant today and worth reading at least once every month. Why?

It's a great way to evaluate your organization

If you're an individual PM, this document is a great way to judge the quality of your product organization.

- Is your organization thriving for the Good Product Manager items or do you hear too often the Bad Product Manager ones?

- If you're not responsible for right product / right time, who in your organization is? If you can't identify that person, your company has a problem. Can you grow into that role?

- If your manager thinks this doesn't apply, are there clear expectations for your role?

As a junior PM at an established company, there's only so much you can do to improve your organization. Problem is, when you get started, you don't know what a good one looks like. If your organization looks too far away from the one described here, it's probably not you, it's them. Time to look for a better one.

It's a great ideal to strive for

As a junior PM, this might look overwhelming, but it's close to the current definition of great product leaders. No one in their right mind expect you to be there on day one. But if you want to become great, this is where you need to go.

One thing that's really hard about PM is that you need to sweat the small stuff (helping your team, fighting bugs, writing release notes and documentations) while never keeping your eyes of the prize. Reading Good Product Manager, Bad Product Manager regularly is a great way to avoid getting stuck at a local maximum.

One way this can f**k you up (and a reason why I put it that late in my PM 101 list is by making you try to do too much, on day one. Don't even try! (but take a look at Ken Norton's checklist for that).

As a junior PM, I think it's more useful to:

- count the number of Good Product Manager boxes you check

- strive to grow that number every quarter. Improve the quality of your work. Pick up additional responsibilities. Do more without asking or being asked.

- measure your progress over time

CEO of the Product?

A final word of caution: Perhaps the most well-known -- and controversial -- bit from GPMBPM is that the "Product Manager is the CEO of the Product". There has been some lengthy discussions on Josh Elman's piece about A Product Manager's Job and its comments. I think it's worth a few more clarifications.

As a junior PM, you will definitely not have authority over anything. You'll have to influence without it. You'll be owning things because people realize they wouldn't happen without you. Not because you've been appointed to own them. Get a first few wins under your belt by doing everything it takes to ship your first product

As you're starting, I'd say that a better to read this is "How can I become the CEO of the product? What do I need to do to get there?". Like a CEO's job, PM is a hard job. Don't try to do too much at once but always strive to expand your scope. I hope this helped!

NOTE: There's an expanded version of GPMBPM (attributed to David Weiden) floating out there that adds a few more point. Very worth reading too.

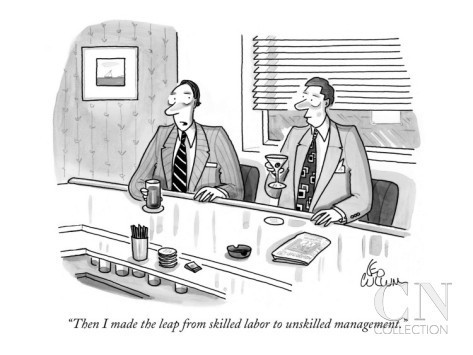

Thanks to Kevin, Léo and Francis for attempting to make sense of my ramblings and to Ben for letting me share his tweets. Cartoon by Leo Cullum for the New Yorker.